We dare to dream again

The choreographer, dancer, and movement trainer Alice Ripoll is one of the most significant figures in contemporary dance within Brazil. Born in Rio de Janeiro, Alice initially pursued studies in psychology before shifting her focus to dance. She combines contemporary dance and Brazilian urban dance in her work, providing dancers with the space to express their own experiences and movement practices. She founded two collectives: REC in 2009 and SUAVE in 2014. Her work has been performed at various festivals in Brazil and throughout Europe, including the Zürcher Theater Spektakel. In August 2024, Alice Ripoll will be a guest at Zürcher Theater Spektakel with her latest work «Zona Franca», that she created together with Copanhia Suave. Our curator and dramaturge Lea Loeb spoke to her, among other things about the creation of the piece in an exciting time of transition.

Alice, you are based in Rio de Janeiro and you have been working with the Companhia Suave for a decade now. I am curious to hear how this collaboration started and how it has developed over the years.

Well, it all started with an invitation from a festival. They asked me to choose a dance style – popular or urban – and gave me 3 months to work on a new piece. I choose the «Passinho» which is regarded by some people as the first purely Brazilian urban dance style. It was created by very young boys from the favelas in Rio de Janeiro and it was quite new at that time.

We held an audition at a cultural centre here in Rio. Subsequently, I decided to collaborate with 10 dancers, most of whom were proficient in passinho, although I was also open to other styles to enable us to blend them creatively. Together, we developed a choreography over the course of three months. During this time, I provided them with lessons in contemporary dance and a bit of theatre, drawing from my experiences working with my previous group and from the research I was doing. As a result, we created a piece titled «Suave»…

…which has been shown at the Zürcher Theater Spektakel in 2015…

Yes. It was during our first presentations that some programmers from Europe decided to invite our piece, which led to our first performance in Zurich. At that time, the dancers were very young, making it quite challenging for me. However, as we continued to receive invitations, we decided to persist as a group, and in 2017, we created our second piece, «Cria». We had no support or sponsorship initially; it was simply our desire to stay together. This is often how things unfold in Brazil. «Cria» also turned out to be a successful piece with numerous invitations. Our current piece «Zona Franca» is our third creation, and it marks the first time we've received international support for a project.

We are very happy to announce that «Zona Franca» will be presented in August at the Zürcher Theater Spektakel. Can you tell us something about the title of the piece? «Zona Franca» means something like «free zone» in English. I guess it refers to the freedom within the choreographic repertoire. Approximately ten distinct dance styles are blended into this piece. But is there another reference to the titel? Does it carry also a political connotation?

Well, let’s say it like this: a «Zona Franca» symbolizes an area where tax obligations are waived. For me this is closely tied to the way the dancers immerse themselves in new languages, both in music and movement, which represents an evolution beyond, what was typical in my generation. We were extremely cautious about avoiding direct imitation of others. We would never have used music without knowing its creator, and we certainly wouldn't have borrowed choreographic elements without permission.

But these young dancers grew up in a different world. Their approach to dance is not an academic one, they never never underwent formal dance training in a school. Instead, they learned entirely from the streets and by copying movements they saw online. As a result, they've developed a distinct technique and style. It's like sampling in music. Brazilian DJs, for instance, often don't create entirely original music; rather, they blend together existing elements. Some may introduce different sounds or adjust the tempo, creating a unique fusion.

There's a sense that true original creation is becoming rare, which is intriguing in its own right. For me, this concept still feels new, and I have thought a lot about it, seeing both positive and negative aspects. An interesting experience occurred during this work when they introduced choreographic elements from other regions of Brazil. I found myself questioning, «Where did you discover this choreography? It belongs to someone else.» It dawned on me that with this group, such distinctions aren't as clear-cut. They draw inspiration from a multitude of sources, and likewise, people are drawn to our work. It's a different dynamic in how we relate to art – kind of a «free zone».

The title can also refer to the way my mind works when I am creating a piece. I draw upon various elements to cultivate a sense of freedom within my imagination. Increasingly, I view my works as destinations I wish to reach, with each journey becoming more accessible. Rather than striving for a specific meaning or narrative, my approach is more associative. You have to know that there's a play on words here with the term «zona» in Portuguese, which can mean both «zone» and «mess», depending on the context. So «Zona Franca» can also mean a big mess, you know.

At the time you were developing the piece, the pandemic was just coming to an end.

Here in Brazil, Covid was even more devastating compared to Europe, mainly due to our political context. So meeting people afterwards felt like emerging from a war zone. I mean, financially, it was tough, especially because we didn't receive adequate support. The assistance provided was insufficient for anyone to live on. A lot of artists did not survive the pandemic times – not just figuratively, but also in reality. When faced with these tragedies in their lives, people reacted in various ways. Some choose to pursue different paths. Others found strength in the situation and felt driven to create even more.

It's fascinating how, during that time, we all began to change somehow. The dynamic of our group had shifted, becoming weightier, laden with a sense of experience etched into us like scars. And then, there was this collective sense within our group, as if we were reaching a turning point. This feeling intensified as our country prepared for the elections. In the weeks leading up to it, nobody seemed able to focus on anything else. The tension was palpable, unlike anything I had ever experienced in my 44 years in Brazil.

You are referring to the presidential elections in 2022, when left-wing former leader Luiz Lula da Silva challenged right-wing populist president Jair Bolsonaro.

Yes. In the weeks leading up to the elections, we worked in our rehearsal room, but our conversations always turned around the political situation, making it difficult to concentrate. It felt like our collective consciousness was consumed by the tension of the moment. I believe this experience heavily influenced our work, subtly shaping its direction. It forced us to confront us with questions about turning points, about the nature of choice and the paths we take as individuals and as a society. What will you do if your country choses a path of destruction? How will you react? Are you able to react? How can we respond, both collectively and individually? These questions permeated our thoughts, seeping into our everyday lives.

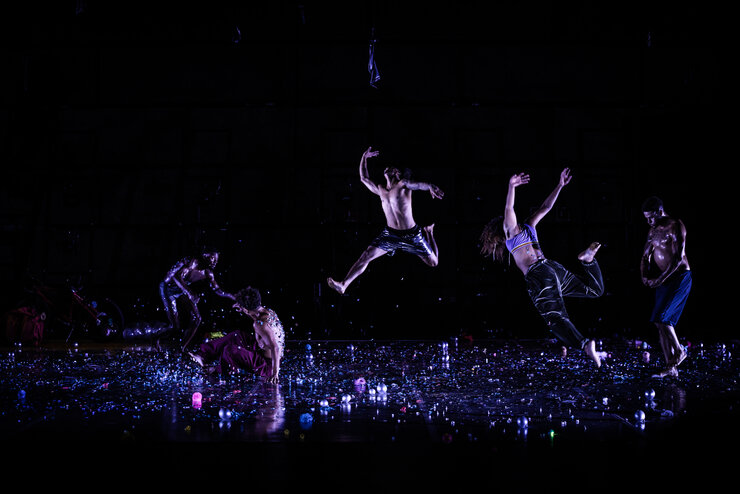

Though not explicitly addressed in our piece, this tension was undeniably present, underscoring the underlying themes and emotions woven into our work. In the performance, we have a lot of balloons exploding on stage. They signify a shift in everything, a profound change not just in the atmosphere, but also within each person's being.

However, this element of transformation wasn't solely tied to Brazil's political landscape. It was also apparent within our group, particularly given that the group has been in existence for about a decade now. There was a moment when I looked at each member, reflecting on their individual strengths and contemplating how to translate this onto the stage. It's remarkable to witness their creativity flourish over the years, reaching a peak where you're inspired to collaborate for a lifetime and create numerous pieces together. Yet, the reality is, you can't hold onto it forever. Life offers no guarantees, and at certain points, individuals may diverge into new, intriguing directions or even become agents of destruction. It's a reminder that change is inevitable, affecting not just us but everyone around us.

Would you say this notion of transformation is the essence of the piece?

I find it quite challenging to articulate the essence because there are so many layers. It feels like there are almost ten different pieces converging simultaneously, each one representing a crossing point for me. Perhaps this intertwining is where the essence truly lies.

I really like «Zona Franca» because it has so many interesting facets: It shows this impressive group dance scenes, but also intimate moments, even some sad moments, that feel like a hangover after a party. Also there are not only dance scenes on stage, but also a bicycle is engaged.

Yes, the bicycle has a bag attached to it, resembling a food delivery setup. This was something that became very prominent here in Brazil, and I believe around the world as well. In Brazil, it significantly increased the number of individuals working in this capacity. We even coined a term for it: «uberization», stemming from services like Uber Eats and Uber in general, but extending to various other job sectors. You see this process of «uberization» happening globally – it's an economic trend. The group I work with is comprised of individuals who have experienced poverty in their childhood and families. So, after the pandemic, the impact of «uberization» on people's lives became even more pronounced and significant. I felt strongly that this needed to be reflected in the piece somehow.

The Zurich audience can certainly look forward to a huge colourful and beautiful celebration of being together, of movement, and of being alive.

Yes, luckily, towards the end of the rehearsal process, we were already seeing signs of hope. It was almost tangible, like we could speak of the future with optimism. We could dare to dream again. I believe that if the opposite had occurred, if things had gone differently, the outcome would have been vastly dissimilar. Also, the easing of Covid restrictions and the return to normalcy, back to work, contributed to this sense of celebration.

However, it's important to acknowledge that the challenges still persist. The issues, particularly the ones prevalent in Brazil, are far from resolved. There's still a need for caution.

Credits

Interview: Lea Loeb